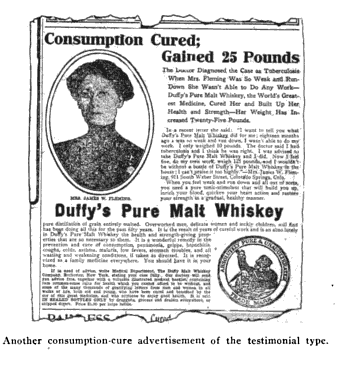

Sometimes I think that I’ve run out of things to blog about and then, I come across an old forgotten book that I think people might enjoy reading. This article concerns Duffy’s Malt Whiskey, made in Rochester, New York, in the early 1900s. Duffy’s claimed to cure everything from consumption to epilepsy. Of course it didn’t cure anything and was nothing more than a low grade whiskey. It is one story among many pertaining to nostrums: a medicine of secret composition recommended by its preparer but usually without scientific proof of its effectiveness.” (1) The American Medical Association tried to bring the “evils of nostrums and quackery” to the attention of the public by pointing out that these remedies didn’t work even though the companies selling them used testimonials as proof that their remedies did work. The testimonials were always proven to be fake. The following excerpts and pictures are from the book, Nostrums and Quackery.

DUFFY’S MALT WHISKEY

“What is this widely advertised nostrum sold as a ‘consumption cure,’ claimed to be the ‘greatest known heart tonic’ and a preparation that ‘builds up the nerve tissues, tones up the heart, gives strength and elasticity to the muscles and richness to the blood?’ The answer to this question will be found to depend, apparently, on when it is asked. During the Spanish-American war Duffy’s Malt Whiskey qualified as a ‘patent medicine’ by the payment of the special tax that was put on nostrums as a means of raising revenue. In a circular issued at that time by the Treasury Department it was stated: ‘The Duffy Malt Whiskey Company have, by evidence under oath filed in this office, shown that their compound called ‘Duffy’s Pure Malt Whiskey’ is composed of distilled spirits in combination with drugs. The claim made by the Duffy Malt Whiskey Co. that their nostrum ‘cures consumption’ is as false as it was cruel. On the other hand, even while the Federal Government was declaring the stuff a ‘medicine,’ the Supreme Court of the state of New York decided that Duffy’s Malt Whiskey was not a medicine but a liquor and that persons selling it would be required to pay the same excise tax and to procure the same liquor-tax certificate that were required of the sellers of any other whiskey. The way in which the New York courts came to pass on this question is an interesting chapter in ‘patent medicine’ history.” (2)

“DUFFY’S PURE MALT WHISKEY CURES CONSUMPTION. All druggists and grocers, $1 a bottle. Medical booklet free. Duffy Malt Whiskey Co., Rochester, N.Y.”

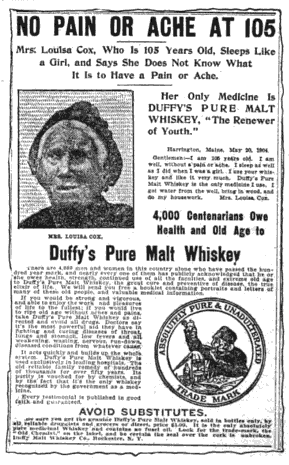

“ ‘I will be one hundred and six years old,’ writes Mrs. Tigue, ‘on the fifteenth of March, and really I don’t feel like I am a day over sixty, thanks to Duffy’s Pure Malt Whiskey. Friends say I look younger and stronger than I did 30 years ago. I have always enjoyed health and been able to eat and sleep well, though I have been a hard worker. Even now I wait on myself and am busy on a pretty piece of fancy work. My sight is so good I don’t even use glasses. Am still blest with all my faculties. The real secret of my great age, health, vigor and content is the fact that for many years I have taken regularly a little Duffy’s Pure Malt Whiskey, and it has been my only medicine. It’s wonderful how quickly it revives and keeps up one’s strength and spirits. I am certain I’d have died long ago had it not been for my faithful old friend ‘Duffy’s.’ August 10, 1904.” (2)

“The sincere and grateful tribute of Mrs. Tigue to the invigorating and life-prolonging powers of Duffy’s Pure Malt Whiskey is one of the most remarkable and convincing on record. She sews, reads and is dependent upon no one for the little services and attentions of old age. Mrs. Tigue’s memory is perfect, and her eyes sparkle with interest as she quaintly recalls events that have gone down into history of the past hundred years. Instead of pining, as many women half her age, she is firm in the belief that with the comforting and strengthening assistance of Duffy’s Pure Malt Whiskey she will live another quarter of a century.” (2)

“The following is the statement referred to, made by Mr. Tigue: Lafayette, Nov. 21, 1905.

‘To Whom it May Concern: I am the son of Mrs. Nancy Tigue, who is now an inmate of the St. Anthony’s Home, and I am 58 years old. My mother is one hundred and five years old, was born in Ireland. Our home is, or was, 413 S. 1st St., Lafayette. Mother is almost blind, and she has been cared for by the Sisters about four years – one year at the Old People’s Home. My mother never drank any intoxicating drinks at all. She does not know what Duffy’s Malt Whiskey is. She was imposed on in order to obtain the advertisement of Duffy’s Malt Whiskey, being nearly blind was influenced to sign a false affidavit by Duffy’s solicitor, which was published without our knowledge or consent.

Michael G. Tigue.'” (2)

“We may accept the statement of the state chemists of North Dakota that the stuff is plain alcohol with syrup added to give it ‘smoothness’ and coloring added to make it look like whiskey; or we may believe the federal chemist who declared it simply ‘whiskey of a very poor quality’; or we may think that Chemist DeGuehuee was right when he said it was ‘whiskey, with a little cane sugar added to it’; or we may prefer Dr. DeGuehuee’s later pronouncement that the stuff ‘is free from added sugar’; again we may feel that Dr. Curran’s early declaration is worthy of attention and that Duffy’s Malt Whiskey contains drugs and is ‘a medicine’ or possibly we may take Dr. Curran’s later statement that the product is merely a whiskey as defined by the Pharmacopeia. But whether we consider Duffy’s Malt Whiskey a ‘patent medicine’ or a low grade ‘booze’ makes little difference. As we have said elsewhere: A high grade whiskey has but a limited place in therapeutics; Duffy’s Malt Whiskey has none. – (From The Journal A. M. A., Nov. 23, 1912.)” (2)

“In the latter months of 1905 the first of a series of articles appeared in Collier’s, dealing with what was well named the Great American Fraud – that is, the nostrum evil and quackery. These articles ran for some months and, when completed, were reprinted in booklet form by the American Medical Association. Tens of thousands of these books have been sold and there is no question that the wide dissemination of the information contained in the Great American Fraud series has done much to mitigate the worst evils of the ‘patent medicines’ and quackery. How hard these forces of evil have been hit is indicated by the organized attempt on their part to discredit and bring into disrepute the American Medical Association by means of speciously named ‘leagues,’ organized by those who are now or have in the past been in the ‘patent medicine’ business, ostensibly to preserve what has been miscalled ‘medical freedom.'” (2)

“Many of the articles that have appeared in The Journal of the American Medical Association during the last few years, dealing with quackery or ‘patent medicines,’ have been reprinted in pamphlet form for distribution to the laity. As the number of these pamphlets increased, it was thought desirable to bring all this matter together in one book. The present volume is the result. Mr. Adams’ ‘Great American Fraud’ articles aimed to cover the whole subject of quackery and the nostrum evil in as broad and general a way as possible. From the nature of the case, it was impossible to give very much space to any one fraud. The present book differs in just this respect from the Collier’s reprint. While but comparatively few concerns are dealt with, they are shown up with special reference to the details of their fraudulent activity. By this means light has been thrown into the innermost recesses – the holy of holies of quackery. It is believed that a perusal of the cases here presented will so plainly show the fraud, the greed and the danger that are inseparable from ‘patent medicine’ exploitation and quackery that the reader must perforce be protected in no small degree from this widespread evil.” (2)

“Just a word as to the distinction made between proprietary medicines and ‘patent medicines.’ Strictly speaking, practically all nostrums on the market are proprietary medicines and but very few are true patent medicines. A patent medicine, in the legal sense of the word, is a medicine whose composition or method of making, or both, has been patented. Evidently, therefore, a patent medicine is not a secret preparation because its composition must appear in the patent specifications. Nearly every nostrum, instead of being patented, is given a fanciful name and that name is registered at Washington; the name thus becomes the property of the nostrum exploiter for all time. While the composition of the preparation, and the curative effects claimed for it, may be changed at the whim of its owner, his proprietorship in the name remains intact. As has been said, a true patent medicine is not a secret preparation; moreover, the product becomes public property at the end of seventeen years. As the term ‘patent medicine’ has come to have a definite meaning to the public, this term is used in its colloquial sense throughout the book. That is to say, all nostrums advertised and sold direct to the public are referred to as ‘patent medicines’; those which are advertised directly only to physicians are spoken of as ‘proprietaries.'” (2)

SOURCES:

1. Merriam Webster Online Dictionary.

2. Cramp, Arthur J. M.D., Nostrums and Quackery, Press of American Medical Association, Five Hundred and Thirty-Five North Dearborn Street, Chicago, 1921, Duffy’s Malt Whiskey, Pages 499-510. Preface, Pages 5-6.