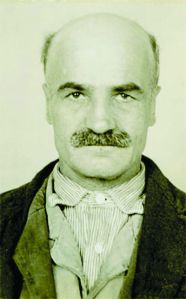

On Saturday, May 16, 2015, LAWRENCE MOCHA was honored and remembered as a living, breathing, contributing member of society, 47 years after his death, with a lovely service and memorial. LAWRENCE was a patient at The WILLARD STATE HOSPITAL and served, unpaid, until the age of 90, as the gravedigger for the institution for thirty years. He dug 1,500 graves for his fellow patients, all of whom, with the exception of one other man, remain in anonymity. As you will see in the video below, it was a beautiful celebration of life that not only remembered with dignity and grace MR. MOCHA but all of the nearly 6,000 patients buried in anonymous graves at the 30 acre, WILLARD STATE HOSPITAL CEMETERY.

I was honored to be invited to this special event but I was unable to attend. I did however view the entire 55 minute video. I was so happy to see that so many people attended the celebration! I understand that there was quite a traffic jam and the State Police had to be called to divert people away from the WILLARD CAMPUS that held their annual tour and fundraising event for the Day Care Center. I hope in some small way I was able to help get the word out with my book and this blog about the dehumanizing, anonymous graves in former NEW YORK STATE HOSPITAL and CUSTODIAL INSTITUTION CEMETERIES.

After viewing the video, there are a few thoughts I would like to share:

- The anonymous graves at WILLARD would never have been brought to light, and the suitcases found in the attic would never have been saved and preserved without the tireless work of CRAIG WILLIAMS, Curator of History at The New York State Museum at Albany.

- “The Lives They Left Behind, Suitcases From A State Hospital Attic” written by DARBY PENNEY and PETER STASTNY, opened the eyes of the public and made us aware of what it was like to be institutionalized. This book inspired so many people, including me, to try to correct the disgrace of anonymous burials in former New York State Hospitals and Custodial Institutions. It led me to ask my State Senator, Joe Robach, to draft a bill concerning the release of patient names, dates of birth and death, and location of grave. Written in 2011 and first introduced to the New York State Senate on March 23, 2012 as S6805-2011, on January 13, 2013 as S2514-2013, and on January 7, 2015 as S840A-2015. As of today, it has not passed into law.

- In 2011, The Willard Cemetery Memorial Project was formed. God Bless all the volunteers who made this celebration possible!

- JOHN ALLEN, Special Assistant to the Commissioner of the New York State Office of Mental Health (518-473-6579), verified in his statements on the video exactly what I have been stating for years! Thank you, Mr. Allen! He told the story about how difficult it was to match A NAME, ANY NAME, with the correct family especially after multiple generations have passed since the ancestor’s death. He spoke about how problematic it was to find a living relative of the deceased buried in a numbered grave (which is exactly why the Federal HIPPA Law changed in March 2013). I know I’m going to hell for saying this, but it gave me great pleasure watching MR. ALLEN getting choked up as he told his story. Hopefully, he now knows what it feels like to search, and search, and search for a “long, lost relative” and finally finding them. MR. ALLEN also had a photograph of MR. MOCHA which he could show to a long, lost family member. Most of us don’t have that luxury even though photographs were taken of each patient. I would love to have a photograph of my great-mother. It’s simply outrageous that one government agency has the right to withhold the names, dates of birth and death, and location of graves of THOUSANDS!!! We’re not talking about medical records here, only the most basic of information concerning the death and final resting place of our loved ones who happened to live and die in a NEW YORK STATE HOSPITAL or CUSTODIAL INSTITUTION.

A NAME IS JUST A NAME AND MEANS NOTHING TO ANYONE UNLESS YOU’RE THE ONE SEARCHING FOR THAT LOVED ONE! It’s just a name that many other people share, it’s just a birth date, it’s just a death date. NO FAMILY WILL BE STIGMATIZED unless they are like me and tell the world that their great-grandmother lived and died at a state hospital. Remember that when WILLARD opened in 1869, that people were really poor, something that we have a hard time understanding today. Some families did not have the money to ship their relatives’ remains home. To believe that none of these people were loved and or missed is incorrect. To think that no one ever attended their burial or said a prayer for them is simply not true.

VIDEO: A MEMORIAL CELEBRATION FOR ALL THOSE INTERED AT WILLARD CEMETERY.

In case you didn’t catch the fifty-one names, beginning at minute 45, here they are.

I apologize in advance if I misspelled your loved ones’ name.

Do these names mean anything to you?

Names Of The Dearly Departed That Were Read In Public And Recorded On Video At: The Willard Memorial Celebration Saturday, May 16, 2015

1889

June 3 – Hannah Thompson

August 14 – Eliza Delaney

October 16 – Ida Bartholomew

1890

September 9 – James Foster

September 15 – Patrick McNamara

October 31 – Mary Champlain

1891

April 26 – Sophia Anderson

May 26 – Mary Brown

June 23 – Katherine Davis

November 16 – Lavinia Hayes

1892

January 4 – Electa George

June 7 – John Van Horne

September 24 – Mary Church

October 20 – Sarah Scott

1893 January 20 – Susan Dugham

September 26 – John B. Kellogg

December 12 – Effie Risley

1894

January 1 – Syble Pollay

February 19 – Suzanne Klinkers Waldron

March 26 – Carolyn Gregory

June 23 – Elizabeth Weber

August 21 – Sarah Ann Baker

November 8 – Sarah Jane Hemstreet

December 30 – Willis Mathews

1895

February 2 – Sophia Podgka

July 21 – Elizabeth Dawson

November 26 – Parmelia Baldwin

1896

March 3 – Ann Dady

1897

April 27 – Miriam D. Bellamy

1898

August 10 – Julia Holden

1899

November 15 – Delia Richards

December 4 – Genevieve Murray

1900

February 3 – Ellen Jane Roe

May 14 – Honora Nugent

July 1 – Harriet Gray

October 12 – Lottie Sullivan

1901

September 19 – Rachel Tice

1902

August 24 – Emma P. Sandborn

1903

April 18 – Elizabeth Snell

December 3 – Nora Murphy

1904

February 20 – Catherine Walwrath

March 18 – Margaret McKay

April 27 – Ellen Horan

June 21 – Isabella Pemberton

October 29 – Mary J. Chapman

December 20 – Mita Mulholland

1905

August 4 – Susan Stortz

September 7 – Mary Gilmore

October 25 – Adele Monnier

1906

April 11 – Sarah Rooney

1968

October 26 – Lawrence Mocha