By 1880, New York State was overwhelmed with the immigrant pauper insane population which by its own laws, was required to care for them. The state legislature enacted new laws allowing for the deportation of this “dependant, defective and delinquent class” of immigrants in order to relieve the state of its financial burden. One of the problems that resulted from the actions of the state legislature was that the sick, blind, deaf and dumb, crippled, feeble-minded, and insane class of immigrants, were sent back to their original port of departure in Europe by themselves with little or no money, and many were sick and improperly clothed. No one bothered to make sure that these helpless people actually made it back to their homes, which in many cases was quite a distance from the port. Many of their relatives and friends never saw or heard from them again. Without the efforts of Miss Louisa Lee Schuyler and The State Charities Aid Association in 1904, this problem may never have been brought to light. On February 20, 1907, the problem was resolved with a new immigration law.

Immigrants Aboard Ship 1902

State Charities Aid Association of New York 1904

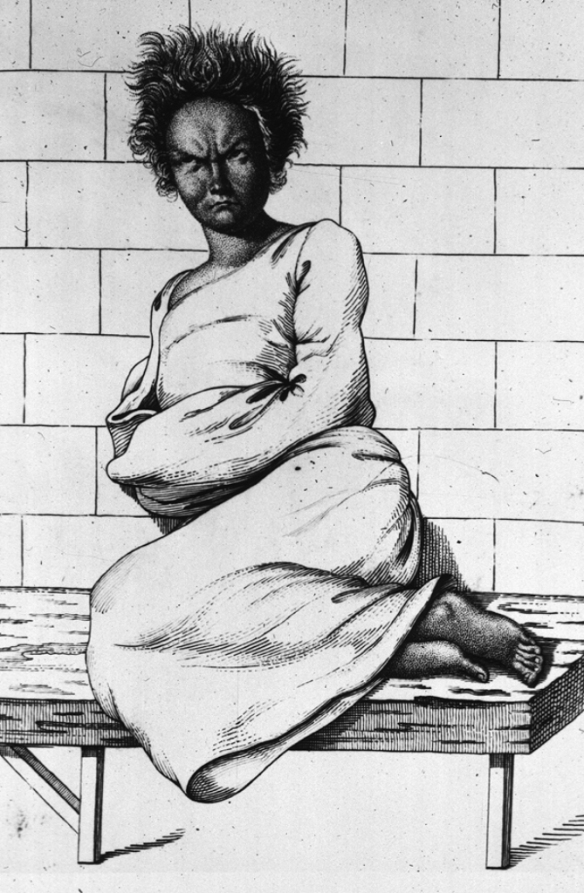

“The United States immigration regulations exclude from admission into the United States insane persons, persons who have been insane within five years previous to landing, and persons who have had two or more attacks of insanity at any time previously. Any alien of these classes who succeeds in entering the United States, or any person who becomes a public charge from causes existing prior to landing, may be deported at any time within two years after arrival, at the expense of the person bringing such alien into the United States. Under certain conditions, the secretary of the treasury is authorized to deport such aliens within three years of landing. Under the provisions of this law 147 insane persons were deported to foreign countries from the State of New York during the fiscal year 1903.

From different sources it came to the attention of the Association that insane aliens deported by the government did not always reach their homes so promptly as they should, and sometimes not at all. In this connection the following quotation from the annual report of the superintendent of the Manhattan State Hospital, West, for the year just closed is significant:

‘While perhaps, it is a matter that does not officially concern the hospital, I desire to state, that I have received several communications from the relatives of patients deported, who claim, up to four or six weeks after such deportation, they have been unable to find that they have arrived at their homes, and could obtain no trace of them. Any conditions which do not afford protection to the insane alien until she reaches her home, are indeed unfortunate, and it appears to me, that some steps should be taken by the proper authorities, toward remedying these matters. The steamship companies do not appear to hold themselves responsible beyond the port where the patient was originally received aboard their steamship.’

The Association, therefore, has made some inquiry into the methods pursued in the deportation of insane aliens, and although it has been possible as yet to make only a cursory examination of a few cases, the conviction is inevitable that the methods of deportation are not such as to afford the patients proper care and protection in all cases, nor to do justice to their friends and relatives. Only five cases have been studied. A brief account of three of the five cases which are at all complete will give some idea of present methods.

1. ‘Case of M.S., a young woman, aged 29 years, a native of Finland, arrived in this country November 1, 1902. About a year and a half later she became insane and was committed to the Manhattan State Hospital, West, April 14, 1904, where she was visited the following week by her friends, the matron and missionary of the Immigrant Girl’s Home. Hearing that the girl was to be deported, these friends offered to arrange for her deportation, hoping to find some woman returning to Finland who would take charge of her. Ten days after this, before the girl’s friends had had time to move in the matter, they received a notice from the hospital that she was to be deported in three days. The names and addresses of the girl’s relatives in Europe were not in the possession of the hospital nor of the steamship company which was to take charge of her, and how she was expected to reach her home, the Association has been unable to discover. The friends of the girl, at the suggestion of the Association, procured these names and addresses, and gave them to the purser of the steamer on which she was to sail, and the Association took the precaution of sending the information to the home office of the steamship company in Glasgow, and of asking the officials there for some particulars regarding the method of transporting the patient from Glasgow to Finland. The following extract from the steamship company’s reply shows the methods employed:

‘Immediately on landing at the dock she was taken to a boarding house where she was properly taken charge of, being attended to by the women of that house. We are forwarding her to-night in charge of our shore interpreter to Hull, and he has instructions to see her safely on board the steamer for Helsingfors, which leaves Hull to-morrow. We have also addressed letters to the owners of the steamer, both in Hull and in Helsingfors, with a request to take some interest in the case, and to give the necessary instructions regarding treatment on board.’

A letter received by the girl’s friends in New York from the girl’s sister in Finland says that no communication was ever received by the friends in Finland from the steamship company, or from any one except the New York friends. The sister writes that she spent three days going from place to place trying to get information regarding the whereabouts of the patient, and finally located her in the Helsingfors hospital for the insane, where she had presumably been sent by the steamship company. This was in July, – two months after the girl sailed from America. The latest letter received from the patient’s sister came in October, and mentioned that she had been unable to find the trunk which was sent with the patient by the New York friends, and which contained all her possessions. The steamship company seems to have done nothing to see that the patient’s property followed her to the hospital.

The features of this case to which we would call attention are these: The failure of the hospital to cooperate with the friends of the patient in providing for her deportation, though no great haste was necessary, as the time in which she could be deported would not expire for six months; the failure of the authorities of this State to take any responsibility for the patient after she had been handed over to the steamship company, including a failure both on their part and on the part of the steamship company to notify the relatives in Europe, or even to ask her friends in this country to notify her relatives; the failure of the steamship company to make any effort to secure the names and addresses of the girl’s family or to make any use of them when furnished by others; the lack of proper care and protection shown in sending an insane person to a boarding house instead of to a hospital, and in forwarding her by night, in the company of a male attendant, on a long railroad journey. It would be interesting to know how this girl fared from the time she left Glasgow in May until her friends found her in July and how she would have fared if her friends in this country and this Association had not actively interested themselves in her case.

2. Case of M.R., an Austrian girl, aged 20 years. The following account of this case was given by the girl’s cousin: ‘When she became insane her brother, who lives in New York city, thought he would send her home, and told the Manhattan State Hospital authorities that he would try to arrange to do this, planning to send her with some acquaintance who was going over. The hospital, however, said that this could not be done; that she was to be returned by the government. The brother was not informed regarding the time of her return until May 3rd, when he received a letter saying that she was to be deported on May 4th. By the time he received the letter she was already on board, and it was impossible for him to go to the steamer that night. He went, however, the next morning about 8 o’clock, and had great difficulty in getting permission to see her. Finally he was allowed to see her for a few minutes. He found her dressed in a cotton wrapper, such as is worn at the State hospital, and provided with no other clothing. He would have brought her clothing if he had known that she needed it, but as nothing had been said by the State hospital it had not occurred to him to do this. He wished to give her money so that she could buy clothing when she got to Hamburg and spoke to the captain about the matter. The captain thought it useless for the girl to have money, but finally consented to take a few dollars for her use.’

The girl was taken to a hospital in Hamburg on landing there, and the parents of the patient were notified by the hospital of her arrival. In this case the significant feature seems to be again the failure of the authorities in this State to co-operate with the friends of the patient for her deportation.

3. Case of F.H. This patient is the son of one of the two sisters whose pathetic story appeared in the newspapers in November, 1904, at the time they committed suicide because of inability to support themselves. The following extract from the newspaper account of the case, though not altogether accurate, gives an idea of the story of the boy: ‘Everything went well with the sisters until a little more than a year ago. Then the boy was taken sick. His illness left him with a deranged brain. He was kept for a time in Bellevue Hospital and then was sent to Ward’s Island. The sisters visited him regularly once a week there. One week, about a year ago, they learned on their regular visit, that he had been sent back to Austria. This, friends of the sisters say, had been done without notification being sent to the mother. Her grief and her fear that some harm would come to him on the voyage were intense. She immediately raised all the money she could get, and, taking also the little which her sister had, she boarded a fast ocean liner for Hamburg. She landed there on the same day that her son landed, and, taking him under her charge, continued the journey to Vienna, where she had him put in an asylum. Then she hurried back to her sister in this country. The strain on the income of the two, however, was too great, and when they got out of work a few weeks ago they became despondent.’

It appears from the records of the Manhattan State Hospital, East, that the boy was admitted there September 25, 1902, and was visited by his mother Sunday, October 5. As he was an alien, having been but nine months in the United States, arrangements were made immediately for his deportation. On October 16, the hospital was informed that the boy would be deported on a vessel sailing October 18, and that he was to be placed on board the 17th. A letter dated October 17 was sent by the hospital to the boy’s mother informing her of his deportation.

Again we note the failure of the State authorities to make any effort to co-operate with the friends of the patient. In this case the hospital did not know of the plans of the Immigration Department for the deportation of the patient until the day before his deportation, and cannot be blamed for not writing earlier to his mother, but under such circumstances it would seem that the friends of the patient should be notified by telegram or special messenger, instead of by a letter, which could hardly be expected to reach its destination before the patient sailed.

To subject insane persons, many of them young and in an acute stage of the disease, to the vicissitudes of a long ocean voyage, with a further journey on the other side of the ocean, is certainly a sufficient risk under the best conditions, and every possible protection should be provided against physical or moral injury. The inhumanity of subjecting relatives of patients to unnecessary anxiety and alarm by leaving them in ignorance of what is happening to those they hold dear, should also be prevented by the establishment of some system which will provide for more personal attention to each case. At present insane aliens are dispatched with little more ceremony than if they were able-minded and able-bodied immigrants, capable of attending to their own interests.”

SOURCE: Reprinted from Twelfth Annual Report of the State Charities Aid Association to the State Commission In Lunacy, No. 89, November 1, 1904, New York City, Untied Charities Building, 105 East 22d Street, Pages 29-34.

To continue reading the rest of the article, click on the PDF file located on the “Interesting Articles & Documents” page.